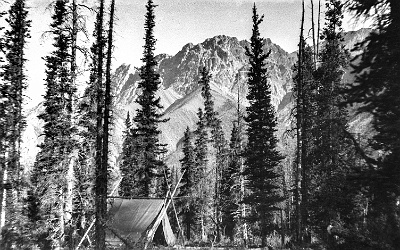

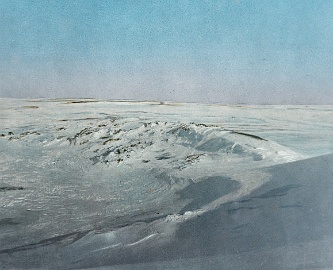

![John Hornby and I made two exploratory trips in 1923. The first to the headwaters of the Little Smoky River, a tributary of the Athabasca; the second to the Columbia Icefield. Our objective was to trace the source of the alluvial gold in the Saskatchewan River. The following [7] photographs were taken during the expedition to the Columbia Icefield. We started from Nordegg, Alberta. DSC04390](thumbs/DSC04390.jpg)

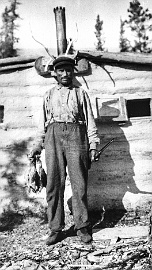

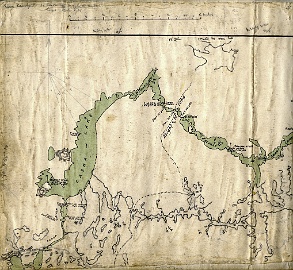

John Hornby and I made two exploratory trips in 1923. The first to the headwaters of the Little Smoky River, a tributary of the Athabasca; the second to the Columbia Icefield. Our objective was to trace the source of the alluvial gold in the Saskatchewan River. The following [7] photographs were taken during the expedition to the Columbia Icefield. We started from Nordegg, Alberta.

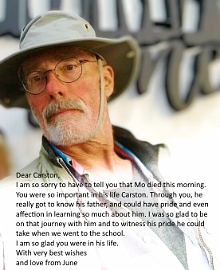

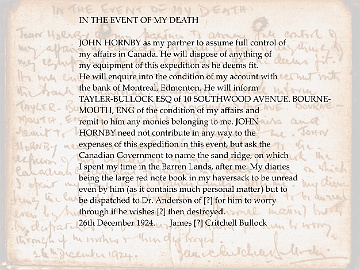

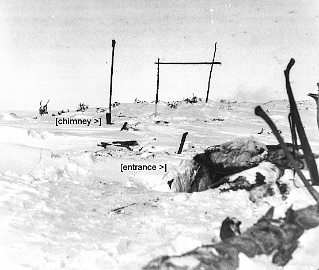

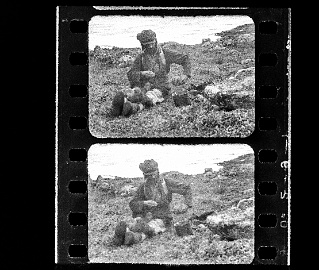

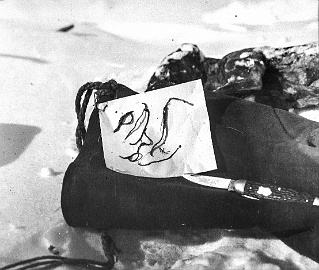

Bullock's will written after Christmas Day 1924 "The most unpleasant day of that long winter for me." Written before he set off into a blizzard that had been raging for days to seek refuge in the Stewart brothers' camp. About to freeze to death if he wouldn't do something.

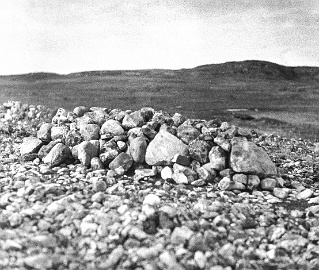

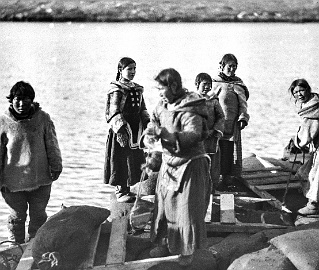

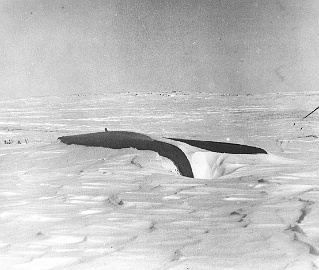

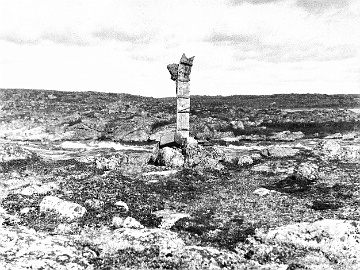

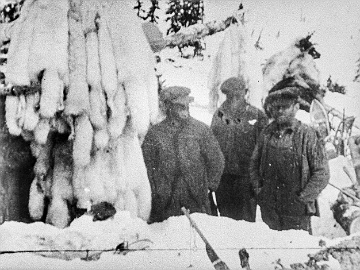

The post carved and erected by the two men who were later murdered by Eskimos. Written on the back of the photograph ‘The last record of Messrs. Radford and Street, murdered by Eskimos at Coronation Gulf. These men were our immediate predecessors in the country.’ For more see: https://www.davidpelly.com/resources/Radford-&-Street-I.pdf & -II.pdf

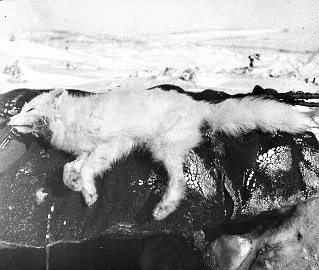

This is the white faced musk oxen (Ovibos Moschatus) of the Arctic Archipelago and Greenland. The species is still fairly numerous in those latitudes. Not my photographs.

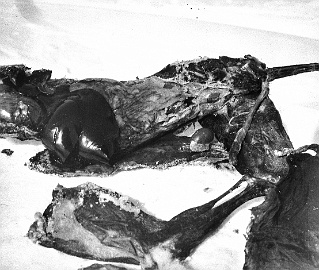

The next photographs were officially considered to be the rarest ever taken in Arctic Canada. Only one Black-faced Muskox (Ovibos Moschatus Moschatus) had ever previously been photographed and in it the animal was barely recognisable. I believe I am correct in saying that the following photographs have never been improved upon, as the animal has not since been seen in such numbers or so close. The species may now be very near extinction.

![View of Thelon River. The clump of trees [?] in which John Hornby and his companions eventually starved to death. DSC04142](thumbs/DSC04142.jpg)

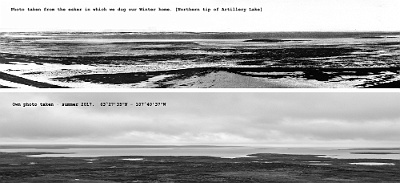

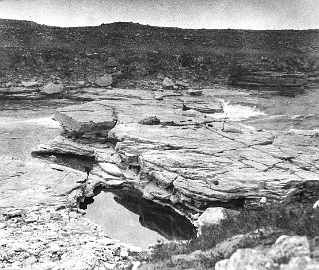

View of Thelon River. The clump of trees [?] in which John Hornby and his

companions eventually starved to death.

companions eventually starved to death.

One of the fierce Arctic Terns swooping down to the attack. This photo goes with the other one, called “Fighting Arctic Terns.” These birds fiercely protect their nesting grounds. They actually pecked the flesh from our faces, and we had to ward off their attacks with our rifle butts.

Short-billed gull. Discovery of this bird on Thelon River created an Easterly record for its known habitat.

Barren Grounds caribou. It has been variously estimated that there are from 10,000,000 to 30,000,000 head of caribou in Arctic Canada. Twice a year they move across the land in great migrations. We saw this colossal sight, but our photographs were ruined by swamping in a rapid. The three that follow actually contain thousands of caribou, but are almost impossible to “decipher”.

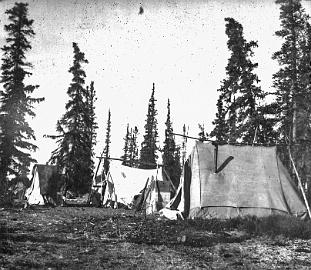

The last of the timber on Thelon River. Then for some hundreds of miles we were back in the Barren Lands proper, using moss for fuel and finding ourselves starving off and on.

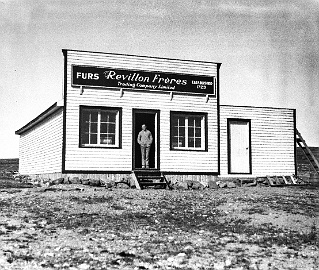

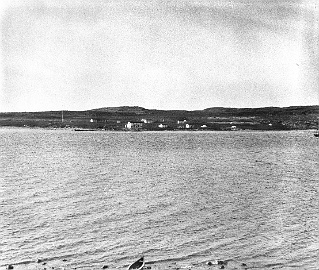

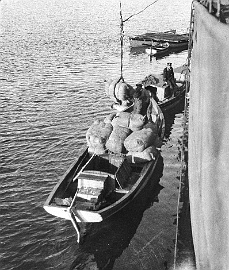

The Trading Post of The Hudson’s Bay Company and Révillon Frères, Chesterfield Inlet, N.W.T. We had travelled by now 1548 miles by canoe and dog sled direct. We had travelled a further 920 miles on side trips. 2468 miles.

![Maggie Nuraklootuk [Alice Nevalinga?]. The heroine in Robt. J. Flaherty’s film “Nanook of the North”, and his son, Barney [Josephie]. At this time Nuraklootuk was crippled with a badly set fractured thigh. Nobody cared. I cursed the [Governor?] of the Hudson’s Bay Company in person later, but doubt that anything was done. DSC04365](thumbs/DSC04365.jpg)

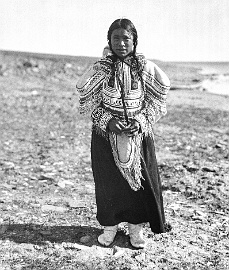

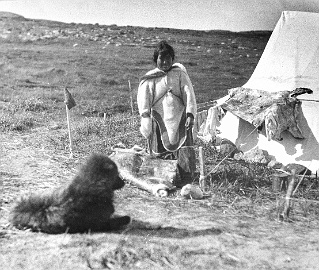

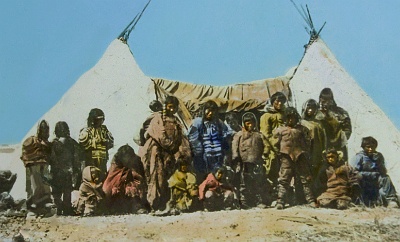

Maggie Nuraklootuk [Alice Nevalinga?]. The heroine in Robt. J. Flaherty’s film “Nanook of the North”, and his son, Barney [Josephie]. At this time Nuraklootuk was crippled with a badly set fractured thigh. Nobody cared. I cursed the [Governor?] of the Hudson’s Bay Company in person later, but doubt that anything was done.

Generated by jAlbum 12.7.2, Matrix 30

![John Hornby [1923]. DSC04392](thumbs/DSC04392.jpg)

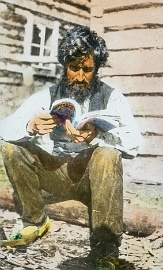

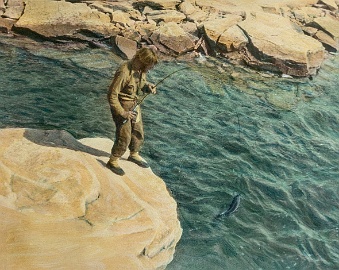

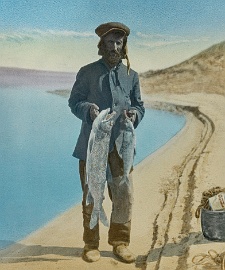

![Captain Bullock showing signs of hardship [hand coloured]. Bullock00014](thumbs/Bullock00014.jpg)

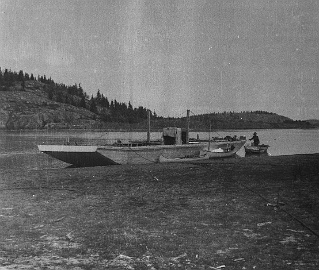

![[On their way to the Barren Lands 1924]. B.C. Mounted Police Post, Fort Fitzgerald, Alta. DSC03862](thumbs/DSC03862.jpg)

![Looking down river from Fort Smith, N.W.T. R. to L. Buckley, Allan Stewart, myself, Al Greathouse. My two canoes prior to leaving alone for Fort Resolution, Gt. Slave Lake. [Bullock's canoe was christened YVONNE. Horby's MATONABBEE.] DSC03868](thumbs/DSC03868.jpg)

![Myself at Fort Fitzgerald. Aged 26. [1924] DSC03869](thumbs/DSC03869.jpg)

![There is a rare heronry on an island among the rapids between Fitzgerald and Smith. This is a young [pelican?] bird floating down the Slave River after leaving its nest. DSC03871](thumbs/DSC03871.jpg)

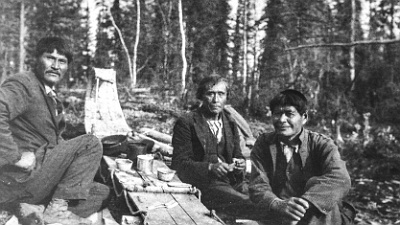

![Indians [?] at Fort Resolution, Gt. Slave Lake, N.W.T. Hornby photo. DSC03873](thumbs/DSC03873.jpg)

![Indians [?] at Resolution. Hornby photo. DSC03874](thumbs/DSC03874.jpg)

![[Panorama stitched together.] Artillery Lake panorama view](thumbs/Artillery%20Lake%20panorama%20view.jpg)

![This is what our fuel supply looked like after the snow had gone. This lot weighed about [?] lbs. DSC03914](thumbs/DSC03914.jpg)

![Sifton Lake N.W.T. View from the esker. This is what the Barren Lands looked like in late June. Slush ice and bare hills. Very difficult for travelling with either canoe or dog sled! [Panorama stitched together] Pano38 39](thumbs/Pano38_39.jpg)

![Gage Falls - Dickson Canyon [Bullock's naming with reference to his dear friend "Yvonne Gage"]. DSC04105](thumbs/DSC04105.jpg)

![The last rapids [Aleksektok] on Thelon River before entering Chesterfield inlet. DSC04345](thumbs/DSC04345.jpg)

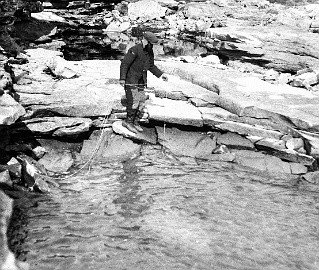

![On the Hanbury River. [Compare with diary entry June 25th,1925, book page 140.] DSC04350](thumbs/DSC04350.jpg)